For Congregation Ner Shalom, November 21, 2014

I will get around to this week's Torah portion, Toldot, in just a little bit. But the thing that has really been pressing on my brain all week long is actually YiddishLand, last week's festival of Yiddish culture here in Sonoma County. It has overtaken all my thoughts, maybe because I've been down sick and repetitive thoughts are what happen to me when I'm down sick. (Better this than some Britney Spears song.)

YiddishLand was amazing. And how it unfolded was amazing. That four people, planning and conspiring over a really short period of time could pull it off; that everyone in the community said yes to everything we asked of them; and that we filled this building with more people than we have ever had, except for High Holy Days. And YiddishLand did, in fact have a kind of High Holy Day feel - a very grand and musical erev followed by an intimate and intense daylight yom experience, an emesdike yiddishe yontev.

YiddishLand was so satisfying, but it was a puzzlement too. As people started snatching up more concert tickets than we have parking spaces in all of Cotati, I began to wonder, what makes this thing so irresistible?

Theories have swirled around in my brain; 600 words of which are appearing this weekend in an Op Ed in the Press Democrat. But trust me, I have more than 600 words-worth of thoughts on this, lucky you.

So why did people respond to YiddishLand with such enthusiasm and joy? Yes, we offered great entertainment and classes. But I suspect what we were selling was not exactly what we thought we were selling. We were offering, for the low, low price of $18 on Saturday and $0 on Sunday, a sense of belonging; an unfettered belonging that a certain large segment of Jews - maybe all Jews, maybe all people - are looking for right at this very moment.

YiddishLand seemed to be a way to touch back into the feel of tribe, without having to get a tattoo or go to Burning Man. It was tribal. It was a safe way to be Jewish. There were no religious requirements - as people assume there are when they come to shul. A synagogue - even a welcoming place like Ner Shalom that doesn't make particular theological demands - is often a locus of religious anxiety, where we sit and feel conflicted about God and tradition and all our clashing values. Even those of us who love and spend our lives inside of Jewish tradition and ritual often find ourselves in a mixed posture: part embrace, part apology. But coming for YiddishLand was something you could do with no apology at all.

And YiddishLand made no ideological demands either. While a century ago Yiddish-speaking Jews might be loudly and angrily debating socialism and communism and the role of literature, those days have passed. What remains in our hands of the Yiddish world is unencumbered by factionalism. And our biggest ideological hotspot right now as Jews - the State of Israel - severed its relationship with Yiddish long ago. So Israel plays no role in the world of Yiddish revival. At YiddishLand, there was no State to promote and no State to defend and no State to krekhtz over, and it felt like a small, guilty, and blessed reprieve.

So the Jews felt free to show up, at least the Ashkenazim did. Well, Ashkenazim and the people who love them. And it was fun. Crazy fun. But the ever-cynical part of me kept wondering if the whole enterprise was just an indulgence in nostalgia. After all, every Jew in the room could - and would, and did - tell you a story about Yiddish, and generally it had to do with family matriarchs and warm childhood feelings. I myself am a shockingly nostalgic person, but I don't want a tribe that is built on that only.

Maybe it's not nostalgia that's the driving force here. It is more a kind of longing to repair something that's broken, to fill in something that's missing. And something is definitely missing for us. There is some kind of transmission that we would have had from our tribe that we didn't get. One disruption of transmission happened when our ancestors arrived, traumatized, on this continent and decided never to speak of the Old Country. Another disruption happened when the next generation used Yiddish as the secret code for the adults instead of as the secret code for the whole family. Another disruption in transmission came when we, our younger selves, decided we didn't want or need any of that Jewish stuff anyway.

A lot of those are turning points we now regret. And now it's time to come back to this week's Torah portion. Because in it, Esau makes a decision about his inheritance that he will later regret. This is the story of Jacob and Esau. Esau is the firstborn, barely, and by law he is the one to inherit both property and blessing from his father. But these are things he doesn't care about in the moment. Jacob, however, is beloved by his mother. Torah tells us he "sits in tents," meaning he's a homebody. (If my kids sat in tents they'd be impressively outdoorsy, but this was another era.) So we might reasonably picture Jacob sitting in the tent at his mother Rebecca's side, as she conveys to him all the family stories and customs. Even before he goes and buys his brother's birthright for a bowl of soup, we could easily imagine him to already be the inheritor of the family transmission. He is invested in the past and seems to have an eye toward posterity. Whereas Esau sees no use for what the past is offering, and seems not to be able to imagine a future where he will begin to care. As it says in the parashah, vayivez Esav et hab'chorah. "Esau disdained his birthright."

Now this is not meant to be a sermon about why can't you be more like Jacob, especially since Jacob frankly doesn't come off so great in this episode. Instead, I want to point out that each of us contains both Jacob and Esau. A part that will do anything to grab hold of our inheritance and the blessing that comes with it. And a part that will let go in exchange for something else that is, at least as far as we can tell in that moment, more important. We have to have both these parts. We could never carry the full life stories and wisdom of every ancestor from every direction. Our lives are not long enough, our brains not ample enough. We must have selective memory. There is no one on the planet who does not choose what they take from the past and what they convey into the future.

The question becomes how we know when to let go. How we know when the sustenance of the lentil soup is greater than the cost to our heritage. Our grandparents withheld their Yiddish from us. For them it was just a language, it wasn't a gateway to a mysterious and forbidden culture. And what they imagined their children and grandchildren could gain by a truly saturated American life was more important to them. Our American-ness was our grandparents' judgment call. They'd lived through 60 generations of outsiderness; this was their chance to fix it. To do something different. To have descendants like us - who could write and sing and design and build and vote. Who could do body work and program apps and be doctors and teachers and astronauts and a million things they'd never heard of and we haven't yet either.

We are our grandparents' judgment call. They dreamed a better life for us. And, for the most part, they dreamed right. And there is loss in that too. Inevitable loss. But not necessarily irremediable loss. And so if, in gratitude for their great ocean voyages and their years of pushing a peddler's cart through city streets, we want to infuse into our lives and our world and our posterity, some of the flavor, some of the language, some of the wisdom of their world, it is entirely our prerogative to reach back and grab what we can for ourselves. Abi gezunt.

And that's not just our grandparents' Yiddish lullabyes or Ladino or Arabic ones either that I'm talking about. There is vastness in our history - mysticism and devotion and learning and custom of a million sorts. Whatever we need to grab and learn and absorb in order to have our feet firmly planted on the ground, in order to feel rooted enough in this rootless time, so that we can weather the storms ahead and flower all the more brilliantly on the other side - they are there for the taking.

We must be both Jacob and Esau. We must grab onto birthright and make it a blessing for us and for this world that we will give birth to. And we must also be willing to let go of what we can't or shouldn't carry. Let go of our hurt. Our pain. Our anger. Whatever keeps us from hope. So that we can feel both belonging and openness. Denseness and expanse. Wisdom and curiosity. So that we will merit a proud yesterday - an eydele nekhtn - and a better tomorrow, a sholemdike morgn.

I am grateful to my YiddishLand collaborators: Gale Kissin, Suzanne Shanbaum and Gesher Calmenson, whose dedication and vision continues to amaze me.

I will get around to this week's Torah portion, Toldot, in just a little bit. But the thing that has really been pressing on my brain all week long is actually YiddishLand, last week's festival of Yiddish culture here in Sonoma County. It has overtaken all my thoughts, maybe because I've been down sick and repetitive thoughts are what happen to me when I'm down sick. (Better this than some Britney Spears song.)

YiddishLand was amazing. And how it unfolded was amazing. That four people, planning and conspiring over a really short period of time could pull it off; that everyone in the community said yes to everything we asked of them; and that we filled this building with more people than we have ever had, except for High Holy Days. And YiddishLand did, in fact have a kind of High Holy Day feel - a very grand and musical erev followed by an intimate and intense daylight yom experience, an emesdike yiddishe yontev.

YiddishLand was so satisfying, but it was a puzzlement too. As people started snatching up more concert tickets than we have parking spaces in all of Cotati, I began to wonder, what makes this thing so irresistible?

Theories have swirled around in my brain; 600 words of which are appearing this weekend in an Op Ed in the Press Democrat. But trust me, I have more than 600 words-worth of thoughts on this, lucky you.

So why did people respond to YiddishLand with such enthusiasm and joy? Yes, we offered great entertainment and classes. But I suspect what we were selling was not exactly what we thought we were selling. We were offering, for the low, low price of $18 on Saturday and $0 on Sunday, a sense of belonging; an unfettered belonging that a certain large segment of Jews - maybe all Jews, maybe all people - are looking for right at this very moment.

YiddishLand seemed to be a way to touch back into the feel of tribe, without having to get a tattoo or go to Burning Man. It was tribal. It was a safe way to be Jewish. There were no religious requirements - as people assume there are when they come to shul. A synagogue - even a welcoming place like Ner Shalom that doesn't make particular theological demands - is often a locus of religious anxiety, where we sit and feel conflicted about God and tradition and all our clashing values. Even those of us who love and spend our lives inside of Jewish tradition and ritual often find ourselves in a mixed posture: part embrace, part apology. But coming for YiddishLand was something you could do with no apology at all.

And YiddishLand made no ideological demands either. While a century ago Yiddish-speaking Jews might be loudly and angrily debating socialism and communism and the role of literature, those days have passed. What remains in our hands of the Yiddish world is unencumbered by factionalism. And our biggest ideological hotspot right now as Jews - the State of Israel - severed its relationship with Yiddish long ago. So Israel plays no role in the world of Yiddish revival. At YiddishLand, there was no State to promote and no State to defend and no State to krekhtz over, and it felt like a small, guilty, and blessed reprieve.

So the Jews felt free to show up, at least the Ashkenazim did. Well, Ashkenazim and the people who love them. And it was fun. Crazy fun. But the ever-cynical part of me kept wondering if the whole enterprise was just an indulgence in nostalgia. After all, every Jew in the room could - and would, and did - tell you a story about Yiddish, and generally it had to do with family matriarchs and warm childhood feelings. I myself am a shockingly nostalgic person, but I don't want a tribe that is built on that only.

Maybe it's not nostalgia that's the driving force here. It is more a kind of longing to repair something that's broken, to fill in something that's missing. And something is definitely missing for us. There is some kind of transmission that we would have had from our tribe that we didn't get. One disruption of transmission happened when our ancestors arrived, traumatized, on this continent and decided never to speak of the Old Country. Another disruption happened when the next generation used Yiddish as the secret code for the adults instead of as the secret code for the whole family. Another disruption in transmission came when we, our younger selves, decided we didn't want or need any of that Jewish stuff anyway.

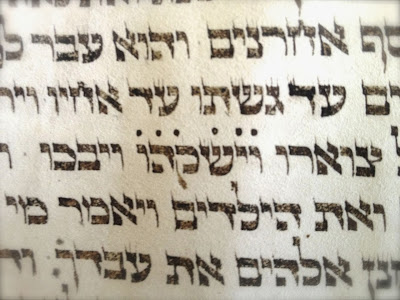

A lot of those are turning points we now regret. And now it's time to come back to this week's Torah portion. Because in it, Esau makes a decision about his inheritance that he will later regret. This is the story of Jacob and Esau. Esau is the firstborn, barely, and by law he is the one to inherit both property and blessing from his father. But these are things he doesn't care about in the moment. Jacob, however, is beloved by his mother. Torah tells us he "sits in tents," meaning he's a homebody. (If my kids sat in tents they'd be impressively outdoorsy, but this was another era.) So we might reasonably picture Jacob sitting in the tent at his mother Rebecca's side, as she conveys to him all the family stories and customs. Even before he goes and buys his brother's birthright for a bowl of soup, we could easily imagine him to already be the inheritor of the family transmission. He is invested in the past and seems to have an eye toward posterity. Whereas Esau sees no use for what the past is offering, and seems not to be able to imagine a future where he will begin to care. As it says in the parashah, vayivez Esav et hab'chorah. "Esau disdained his birthright."

Now this is not meant to be a sermon about why can't you be more like Jacob, especially since Jacob frankly doesn't come off so great in this episode. Instead, I want to point out that each of us contains both Jacob and Esau. A part that will do anything to grab hold of our inheritance and the blessing that comes with it. And a part that will let go in exchange for something else that is, at least as far as we can tell in that moment, more important. We have to have both these parts. We could never carry the full life stories and wisdom of every ancestor from every direction. Our lives are not long enough, our brains not ample enough. We must have selective memory. There is no one on the planet who does not choose what they take from the past and what they convey into the future.

The question becomes how we know when to let go. How we know when the sustenance of the lentil soup is greater than the cost to our heritage. Our grandparents withheld their Yiddish from us. For them it was just a language, it wasn't a gateway to a mysterious and forbidden culture. And what they imagined their children and grandchildren could gain by a truly saturated American life was more important to them. Our American-ness was our grandparents' judgment call. They'd lived through 60 generations of outsiderness; this was their chance to fix it. To do something different. To have descendants like us - who could write and sing and design and build and vote. Who could do body work and program apps and be doctors and teachers and astronauts and a million things they'd never heard of and we haven't yet either.

We are our grandparents' judgment call. They dreamed a better life for us. And, for the most part, they dreamed right. And there is loss in that too. Inevitable loss. But not necessarily irremediable loss. And so if, in gratitude for their great ocean voyages and their years of pushing a peddler's cart through city streets, we want to infuse into our lives and our world and our posterity, some of the flavor, some of the language, some of the wisdom of their world, it is entirely our prerogative to reach back and grab what we can for ourselves. Abi gezunt.

And that's not just our grandparents' Yiddish lullabyes or Ladino or Arabic ones either that I'm talking about. There is vastness in our history - mysticism and devotion and learning and custom of a million sorts. Whatever we need to grab and learn and absorb in order to have our feet firmly planted on the ground, in order to feel rooted enough in this rootless time, so that we can weather the storms ahead and flower all the more brilliantly on the other side - they are there for the taking.

We must be both Jacob and Esau. We must grab onto birthright and make it a blessing for us and for this world that we will give birth to. And we must also be willing to let go of what we can't or shouldn't carry. Let go of our hurt. Our pain. Our anger. Whatever keeps us from hope. So that we can feel both belonging and openness. Denseness and expanse. Wisdom and curiosity. So that we will merit a proud yesterday - an eydele nekhtn - and a better tomorrow, a sholemdike morgn.

I am grateful to my YiddishLand collaborators: Gale Kissin, Suzanne Shanbaum and Gesher Calmenson, whose dedication and vision continues to amaze me.