For Congregation Ner Shalom

So you know that classic cinematic moment, where you have a couple running through a meadow of tall grasses, careening toward each other, inevitably - in fact compulsorily - running in slomo, likely accompanied by the love theme from Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet, and ending ultimately in an embrace, a kiss, sometimes a lift and a spin.

One wonders where this idea started; was it first literary and then translated to screen? And what is the story of these two lovers anyway? If they're so in love, why are they running from opposite directions? And if it's a rendezvous, how did they happen to arrive at just the right moment to fall into each others arms so flawlessly in the most picturesque spot?

Now, I'm not certain I've ever actually seen this in film or TV1; what I've seen are the countless spoofs of it, where they come together and something goes wrong. They bounce off each other, or they miss each other, or they slam into each other and get knocked out. This trope is so cheesy it begs to be satirized. As was done in these words by one Jennifer Hart, submitted to a Washington Post bad metaphor contest: "Long separated by cruel fate, the star-crossed lovers raced across the grassy field toward each other like two freight trains, one having left Cleveland at 6:36 pm traveling at 55 mph, the other from Topeka at 4:19 pm at a speed of 35 mph."

Though not running through a meadow, this week's Torah portion, Vayishlach, contains a kind of comparable moment. Two people who are deeply connected and long parted, heading toward each other through the open spaces, ending in a kiss. Those two people are Jacob and his twin brother Esau, separated for 20 years after Jacob's theft of birthright and blessing and subsequent flight back to the Old Country. Jacob has gotten older. He has 2 wives and 2 concubines. A dozen kids. Flocks. Wealth. And now, God has instructed him to return to his birthplace, to the land of his ancestors, in an almost exact reversal of God's first command to Abraham, to leave his birthplace and his father's house.

Jacob knows that heading toward his past involves facing his brother and the conflict he has dodged for two decades. He is nervous. He sends messages and gifts ahead - flocks and servants. He learns his brother is approaching with a regimen of 400 men and he quakes with fear. He divides his holdings into two camps, so that if Esau should attack, there is the chance that half his household might escape.

Night falls, and Jacob finds himself in a mysterious wrestling match with a stranger - a stranger or an angel, maybe the Archangel Michael, according to some midrash. Or could it be his brother? Or his own conscience (although rare is the conscience that can dislocate your hip)? Emerging from this struggle, Jacob is given a new name - Yisrael, Israel, the one who wrestles with God.

Dawn comes and Jacob, now Israel, sets forth toward his brother. He punctuates the final run up to the rendezvous, bowing to the ground seven times. They get nearer and nearer until Esau can bear it no more and breaks into a run:

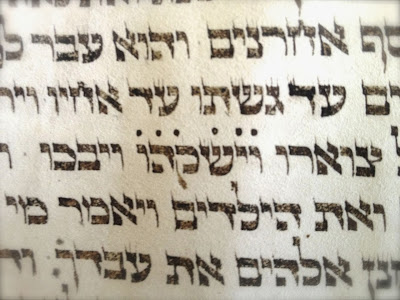

It is perhaps one of the most poignant moments in Torah. Beautiful and unexpected. But there is something else unusual about it, that you only notice if reading from Torah. The word vayishakehu - "and he kissed him" - is written with a dot drawn above each letter, as you can see here:

This is exceedingly rare in Torah, which doesn't actually have any system of dots or diacritics. It is rare, and like everything else in our tradition, of uncertain meaning. Some say that at some point there had been a scribal error or the suspicion of one, and the dots are an indication to take the word with a grain of salt. Others say that the dots indicate that there is cause to look deeper, to look underneath the word.

And so our sages did just that; they looked underneath the word and they decided that Esau's kiss was insincere. That he kissed, but not with a whole heart. Other midrash goes even further. That Esau did not intend to kiss (represented by the root nashak in Hebrew) but rather to bite (represented by the similar root nashakh). And that in the instant that Esau fell on Jacob to bite him True Blood-style, Jacob's neck turned to ivory and Esau's teeth were painfully deflected, causing him, in the next word, to weep.

The distrust of Esau and his motives is captured in the words of the 1st Century Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who actually did believe that Esau was sincere in the moment, but that his love was deeply out of character. Bar Yochai says, "It is halachah" - that is, tradition strong enough to be considered law - "that Esau hates Jacob."

So what is this about? Here we have to turn for a moment to our fables surrounding the origins of the nations of the world. We of course see ourselves as B'nei Yisrael - the Children of Israel, i.e. the descendants of Jacob. We see Ishmael as the forebear of the Arab nations. Esau, or as he is renamed, Edom, is imagined to be the forebear of the Gentiles: the Greeks, the Romans and ultimately all Christians and Europeans. These gentile nations were referred to in our rabbinic tradition as Edomites, as the descendants of Esau. And so Esau and Jacob in this moment, in the rabbinic view, are not just individuals in a family drama, but avatars of the Gentile and Jewish worlds. And already in Bar Yochai's time, we see that the hatred leveled at Jews was so old and entrenched that it was beyond custom: it was like law.

In Bar Yochai's time and throughout our history, an awareness of the threat on our doorstep has been part of our people's consciousness. Our oldest prayers, our psalms, for every beautiful transcendent moment they offer, they boast an equal number of requests for God to destroy our enemies. Even our Shabbat psalm, Psalm 92, read on our holy day, and in which we early on sing l'hagid baboker chasdecha - :let us sing your kindness in the morning;" and which we cap off with tzadik katamar yifrach - "the righteous shall blossom like the date palm;" this Shabbat psalm also has a middle section, which Reb Judith Goleman and I confessed to each other this week we both treat as the great flyover; a middle section in which we say that evildoers blossom solely so that they may be utterly destroyed; that our enemies will be brought to nought. Such prayers for real-world military victory over our enemies has always been part of our tradition, which is ironic when you consider how seldom we've ever had real-world military victory. There were the Maccabbees 2200 years ago. And of course the modern State of Israel. And between them? Well, not so much. Most of our history is characterized by being subject to other people's aggression.

Last week we marked the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the "night of shattered glass," the days-long pogrom that swept through Germany and Austria, days of terror and destruction and hiding that are conveniently used to date the beginning of the Holocaust. But of course it wasn't a beginning; but a continuation. The pogroms, the persecutions, the massacres. They've existed in every generation of our people, if not in one place then in another. We have the good fortune to be living in a time and a place where there is respite; where Anti-Semitism isn't violent or overt. I asked our 12-year old if he'd experienced or witnessed Anti-Semitism in his life. Once, he answered, when playing World of Warcraft, a fantasy computer game in which real people around the world play in a virtual landscape, modeled on a kind of folkloric medieval Europe. There are certain activities in the game that can get a player labeled as a Goldfarmer or a Tradespammer. And sure enough, in a spontaneous replication of medieval European values, Ari had witnessed at least one player calling the Goldfarmers and Tradespammers "Jews." To their credit, other players responded strongly.

I'm not trying to raise an alarm about Anti-Semitism. But instead to note the context in which the rabbis voiced their suspicion about Esau and his motives. They had not had a wealth of experience in which the benevolence of the non-Jewish world was wholehearted.

But it's not just the mere identification of Esau with the gentile nations at work. The physical and characterological differences between the brothers also resonate with a certain Jewish anxiety about what we Jews are like. Esau is a hunter, an activity our grandparents might well call goyim naches, the gentile sphere of brawny activity. And Jacob? While he's not clearly a scholar, which was often the Jewish male ideal pitted against the gentile warrior archetype, he is nonetheless a mama's boy. Esau leads with physical action. Jacob cooks. And when Jacob prevails at taking the birthright and the blessing, it is not by confrontation but by cunning. The portrayal of Jacob, as seen through the cultural lens of a European patriarchy, looks like an indictment of Jacob's masculinity and of Jewish masculinity altogether. As Daniel Boyarin writes in his book, Unheroic Conduct: The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man, "The term goyim naches refers to violent physical activity, such as hunting, dueling, or wars -- all of which Jews traditionally depised, for which they in turn were despised -- and to the association of violence with male attractiveness and with sex itself..."

As Jacob approaches his brother, we see the Jewish people addressing the gentile world, aware that they are despised, that the gentile world sees their shunning of violence as a weakness, as an ugliness, as a failure of manhood.

And yet it is Esau, the hunter, surrounded by a military detail, who falls on his brother's neck and kisses him and weeps. And Bar Yochai says, despite the abiding fact of Esau's hatred of Jacob, Esau kisses him with a whole heart.

This is not the expected end. You expect a duel. My name is Esau son of Isaac. You stole my birthright. Prepare to die.

If Esau represents the unrelenting brutality of the non-Jewish world, he does not make good on the threat. So did he transform as well? Did he have his own wrestling match the night before? Or is this change brought about by 20 intervening years, during which his anger at being bamboozled by his brother gave way to sadness at being abandoned by him?

Or is he more complex, more subtle, than Torah's portrayal of him, and than Jewish anxieties about him? Shoshana Fershtman suggested to me that Jacob wrestled not with an angel but with a shadow, the shadow he'd been projecting onto Esau his whole life. With the shadow defeated, Esau was now able to be seen for who he really was - someone who loved and missed his brother.

And so that day, when they approach each other, when in the last moment Esau breaks into a run like the star-crossed lovers in a bad movie, as they fall into each other's arms, Torah puts dots over each letter of their kiss, slowing the reader down, demanding that we pronounce each syllable separately: va - yish - sha - ke - hu. Torah gives us the requisite slow-motion effect so that we have the chance to look into Esau's eyes and see that he isn't exactly the way we thought of him, and that his heart is truly overflowing. And we get the span of six short breaths to whisper to Jacob that yes, this might be real. And as the film frames tick past we can absorb for a moment that despite history, despite everyone's bad patterns and worst instincts, despite our low, low expectations of the other, something better, a moment of forgiveness, of understanding, is possible. We can never know about someone else's transformation, but we can wrestle with our own shadows, with our own fears, with our own projections, and clear the way to receive the open-hearted kiss. And if we can do this enough, then we can make a better world, where hearts will skip beats from eagerness, not from fear; where hiding will only be required in children's games; and where the sound of shattering glass will emanate only from under the wedding chupah.

So you know that classic cinematic moment, where you have a couple running through a meadow of tall grasses, careening toward each other, inevitably - in fact compulsorily - running in slomo, likely accompanied by the love theme from Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet, and ending ultimately in an embrace, a kiss, sometimes a lift and a spin.

One wonders where this idea started; was it first literary and then translated to screen? And what is the story of these two lovers anyway? If they're so in love, why are they running from opposite directions? And if it's a rendezvous, how did they happen to arrive at just the right moment to fall into each others arms so flawlessly in the most picturesque spot?

Now, I'm not certain I've ever actually seen this in film or TV1; what I've seen are the countless spoofs of it, where they come together and something goes wrong. They bounce off each other, or they miss each other, or they slam into each other and get knocked out. This trope is so cheesy it begs to be satirized. As was done in these words by one Jennifer Hart, submitted to a Washington Post bad metaphor contest: "Long separated by cruel fate, the star-crossed lovers raced across the grassy field toward each other like two freight trains, one having left Cleveland at 6:36 pm traveling at 55 mph, the other from Topeka at 4:19 pm at a speed of 35 mph."

Though not running through a meadow, this week's Torah portion, Vayishlach, contains a kind of comparable moment. Two people who are deeply connected and long parted, heading toward each other through the open spaces, ending in a kiss. Those two people are Jacob and his twin brother Esau, separated for 20 years after Jacob's theft of birthright and blessing and subsequent flight back to the Old Country. Jacob has gotten older. He has 2 wives and 2 concubines. A dozen kids. Flocks. Wealth. And now, God has instructed him to return to his birthplace, to the land of his ancestors, in an almost exact reversal of God's first command to Abraham, to leave his birthplace and his father's house.

Jacob knows that heading toward his past involves facing his brother and the conflict he has dodged for two decades. He is nervous. He sends messages and gifts ahead - flocks and servants. He learns his brother is approaching with a regimen of 400 men and he quakes with fear. He divides his holdings into two camps, so that if Esau should attack, there is the chance that half his household might escape.

Night falls, and Jacob finds himself in a mysterious wrestling match with a stranger - a stranger or an angel, maybe the Archangel Michael, according to some midrash. Or could it be his brother? Or his own conscience (although rare is the conscience that can dislocate your hip)? Emerging from this struggle, Jacob is given a new name - Yisrael, Israel, the one who wrestles with God.

Dawn comes and Jacob, now Israel, sets forth toward his brother. He punctuates the final run up to the rendezvous, bowing to the ground seven times. They get nearer and nearer until Esau can bear it no more and breaks into a run:

וירץ עשו לקראתו ויפל על–צוארו וישקהו ויבכו

Esau ran toward him and embraced him and fell on his neck

and kissed him

and they wept.

It is perhaps one of the most poignant moments in Torah. Beautiful and unexpected. But there is something else unusual about it, that you only notice if reading from Torah. The word vayishakehu - "and he kissed him" - is written with a dot drawn above each letter, as you can see here:

|

| Photo of text from Ner Shalom's torah scroll, which originated in Sobeslav, Czech Republic. |

And so our sages did just that; they looked underneath the word and they decided that Esau's kiss was insincere. That he kissed, but not with a whole heart. Other midrash goes even further. That Esau did not intend to kiss (represented by the root nashak in Hebrew) but rather to bite (represented by the similar root nashakh). And that in the instant that Esau fell on Jacob to bite him True Blood-style, Jacob's neck turned to ivory and Esau's teeth were painfully deflected, causing him, in the next word, to weep.

The distrust of Esau and his motives is captured in the words of the 1st Century Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who actually did believe that Esau was sincere in the moment, but that his love was deeply out of character. Bar Yochai says, "It is halachah" - that is, tradition strong enough to be considered law - "that Esau hates Jacob."

So what is this about? Here we have to turn for a moment to our fables surrounding the origins of the nations of the world. We of course see ourselves as B'nei Yisrael - the Children of Israel, i.e. the descendants of Jacob. We see Ishmael as the forebear of the Arab nations. Esau, or as he is renamed, Edom, is imagined to be the forebear of the Gentiles: the Greeks, the Romans and ultimately all Christians and Europeans. These gentile nations were referred to in our rabbinic tradition as Edomites, as the descendants of Esau. And so Esau and Jacob in this moment, in the rabbinic view, are not just individuals in a family drama, but avatars of the Gentile and Jewish worlds. And already in Bar Yochai's time, we see that the hatred leveled at Jews was so old and entrenched that it was beyond custom: it was like law.

In Bar Yochai's time and throughout our history, an awareness of the threat on our doorstep has been part of our people's consciousness. Our oldest prayers, our psalms, for every beautiful transcendent moment they offer, they boast an equal number of requests for God to destroy our enemies. Even our Shabbat psalm, Psalm 92, read on our holy day, and in which we early on sing l'hagid baboker chasdecha - :let us sing your kindness in the morning;" and which we cap off with tzadik katamar yifrach - "the righteous shall blossom like the date palm;" this Shabbat psalm also has a middle section, which Reb Judith Goleman and I confessed to each other this week we both treat as the great flyover; a middle section in which we say that evildoers blossom solely so that they may be utterly destroyed; that our enemies will be brought to nought. Such prayers for real-world military victory over our enemies has always been part of our tradition, which is ironic when you consider how seldom we've ever had real-world military victory. There were the Maccabbees 2200 years ago. And of course the modern State of Israel. And between them? Well, not so much. Most of our history is characterized by being subject to other people's aggression.

Last week we marked the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the "night of shattered glass," the days-long pogrom that swept through Germany and Austria, days of terror and destruction and hiding that are conveniently used to date the beginning of the Holocaust. But of course it wasn't a beginning; but a continuation. The pogroms, the persecutions, the massacres. They've existed in every generation of our people, if not in one place then in another. We have the good fortune to be living in a time and a place where there is respite; where Anti-Semitism isn't violent or overt. I asked our 12-year old if he'd experienced or witnessed Anti-Semitism in his life. Once, he answered, when playing World of Warcraft, a fantasy computer game in which real people around the world play in a virtual landscape, modeled on a kind of folkloric medieval Europe. There are certain activities in the game that can get a player labeled as a Goldfarmer or a Tradespammer. And sure enough, in a spontaneous replication of medieval European values, Ari had witnessed at least one player calling the Goldfarmers and Tradespammers "Jews." To their credit, other players responded strongly.

I'm not trying to raise an alarm about Anti-Semitism. But instead to note the context in which the rabbis voiced their suspicion about Esau and his motives. They had not had a wealth of experience in which the benevolence of the non-Jewish world was wholehearted.

But it's not just the mere identification of Esau with the gentile nations at work. The physical and characterological differences between the brothers also resonate with a certain Jewish anxiety about what we Jews are like. Esau is a hunter, an activity our grandparents might well call goyim naches, the gentile sphere of brawny activity. And Jacob? While he's not clearly a scholar, which was often the Jewish male ideal pitted against the gentile warrior archetype, he is nonetheless a mama's boy. Esau leads with physical action. Jacob cooks. And when Jacob prevails at taking the birthright and the blessing, it is not by confrontation but by cunning. The portrayal of Jacob, as seen through the cultural lens of a European patriarchy, looks like an indictment of Jacob's masculinity and of Jewish masculinity altogether. As Daniel Boyarin writes in his book, Unheroic Conduct: The Rise of Heterosexuality and the Invention of the Jewish Man, "The term goyim naches refers to violent physical activity, such as hunting, dueling, or wars -- all of which Jews traditionally depised, for which they in turn were despised -- and to the association of violence with male attractiveness and with sex itself..."

As Jacob approaches his brother, we see the Jewish people addressing the gentile world, aware that they are despised, that the gentile world sees their shunning of violence as a weakness, as an ugliness, as a failure of manhood.

And yet it is Esau, the hunter, surrounded by a military detail, who falls on his brother's neck and kisses him and weeps. And Bar Yochai says, despite the abiding fact of Esau's hatred of Jacob, Esau kisses him with a whole heart.

This is not the expected end. You expect a duel. My name is Esau son of Isaac. You stole my birthright. Prepare to die.

If Esau represents the unrelenting brutality of the non-Jewish world, he does not make good on the threat. So did he transform as well? Did he have his own wrestling match the night before? Or is this change brought about by 20 intervening years, during which his anger at being bamboozled by his brother gave way to sadness at being abandoned by him?

Or is he more complex, more subtle, than Torah's portrayal of him, and than Jewish anxieties about him? Shoshana Fershtman suggested to me that Jacob wrestled not with an angel but with a shadow, the shadow he'd been projecting onto Esau his whole life. With the shadow defeated, Esau was now able to be seen for who he really was - someone who loved and missed his brother.

And so that day, when they approach each other, when in the last moment Esau breaks into a run like the star-crossed lovers in a bad movie, as they fall into each other's arms, Torah puts dots over each letter of their kiss, slowing the reader down, demanding that we pronounce each syllable separately: va - yish - sha - ke - hu. Torah gives us the requisite slow-motion effect so that we have the chance to look into Esau's eyes and see that he isn't exactly the way we thought of him, and that his heart is truly overflowing. And we get the span of six short breaths to whisper to Jacob that yes, this might be real. And as the film frames tick past we can absorb for a moment that despite history, despite everyone's bad patterns and worst instincts, despite our low, low expectations of the other, something better, a moment of forgiveness, of understanding, is possible. We can never know about someone else's transformation, but we can wrestle with our own shadows, with our own fears, with our own projections, and clear the way to receive the open-hearted kiss. And if we can do this enough, then we can make a better world, where hearts will skip beats from eagerness, not from fear; where hiding will only be required in children's games; and where the sound of shattering glass will emanate only from under the wedding chupah.

1 I have now been told that this trope originated in the 1967 film "Elvira Madigan." I guess I'll have to Netflix it to see if it's the case; not that I want to. It ends with a dismal double suicide. Oh - spoiler alert. It ends with a dismal double suicide. Goyim naches. See below.