[For Congregation Ner Shalom, January 21, 2011]

I just got back from Los Angeles yesterday, where I spent the early part of the week in a long negotiation with someone who wants to do some business with my other, um, congregation. These were difficult negotiations in some ways. There is possibly a lot at stake, and the person across the table was perhaps more different from me than anyone I've ever had to stare at for 9 hours. He was in many ways a stereotype. That is, there exists a particular stereotype of the tough guy, right out of the Sopranos, and either he fit it perfectly or he played it perfectly. I, of course, am undoubtedly a stereotype in other people's eyes. You know, the singing-drag-queen-slash-rabbi sterotype. But his type is a special challenge for me. I spent my childhood fleeing toughs, and my adulthood building a life in which they do not figure. And yet here he was. I looked at him and he looked at me. And I couldn't figure out how to understand him, so imprisoned was I within the image he was presenting - or that I was projecting.

As I sat there I began to feel sadness over the inability of any of us to really understand each other. After all, what clues are we ever given? Clothes, affect, words. These are such paltry tools. So deficient. How many times a week do we say "that's not what I meant" because the words preceding them were too limited to adequately convey our intent? Even in the mouths of the greatest poets, can words ever communicate someone's wholeness? Or the fullness and complexity of any idea?

|

| Mt. Sinai |

This ability to absorb language fully and unmediated is of major interest to the early Chassidic master, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev. He notes the following verse of our parashah:

בחדש השלישי לצאת בני ישראל מארץ מצרים ביום הזה בא מדבר סיני:

On the third month of the Children of Israel's departure from Egypt,

on this day they came to Midbar Sinai.

Midbar Sinai. The Wilderness of Sinai. But Hebrew is a marvelously squirmy thing. Squeeze midbar enough to change the vowels and you can read it that the Children of Israel came not to the Wilderness of Sinai but to the Speech of Sinai. And this is where he begins his inquiry. What is the Speech of Sinai, he asks, and he answers.

The speech of Sinai is language that carries not just the simple and limited meanings of the words but all their possible meanings as well. There is dibbur - the actual words recorded in Torah, and kol - the voice - God's voice, which includes all the associated thoughts about the words, all the Masechot of Talmud discussing the words. In the mouth of another rabbi, this idea could simply be a defense of the holiness of the Talmud. "See? God delivered that too at Sinai."

But Levi Yitzchak is much more expansive. He doesn't limit the content of God's voice to a specific canon. God's voice, rather, is infinite. For Levi Yitzchak, the Speech of Sinai is language in which word and voice, dibbur and kol, are the same. Language through which we hear with fullness, with completeness. No distinctions between surface structure and deep structure, between form and meaning, between pshat, the simple meaning and drash, the interpretation.

And where Talmud requires the tools of scholarship to access it, Levi Yitzchak sees God's kol, the greater meaning, as something available to anyone with the proper mindfulness. He says:

כשאדם מאמין שכל הבלים והדיבורים היוצאים מפיו הם הכל כח וחיות הבורא, ו'רוח ה' דיבר בו', ואז כשמקשר הדיבור בקול, והכל במחשבה בשורש הרוחני וחיות אלהות, אז אף אל פי שאין הדיבור יכול לכלול כמה דיבורים, יכול הוא להיות מכמה ענינים וכמה שכליים והדיבור מתפוצץ לכמה חלקים , כיון שהוא דיבור אלהים.

If you believe that your breath and words draw on the power and vigor of the Creator, such that the Spirit of God speaks through you, you will thereby connect the words and the voice, and if in your thought it all derives from God's spiritual source, then the words give way to multiple thoughts and understandings, and the dibbur, the speech, explodes into multiplicity, for it is the speech of God.In other words, holding an awareness of their divine source turns the spoken words into something much bigger and deeper and multicolored. Mindfulness of the divine source of everything opens the floodgates of meaning. The word embodies its full meaning; the fragment implies the whole.

|

| La Grande Jatte |

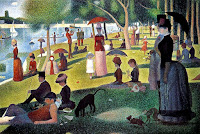

Side story. Over the winter holidays, my family set about working on a jigsaw puzzle. Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Isle of la Grande Jatte in 1000 pieces. As is not uncommon, the borders were quickly assembled, constituting by my math about 12.5% of the overall puzzle or 100% of the fun part. Then interest waned. The pieces lingered on the coffee table for a fortnight and were then returned to their box. Monday, at Oakland Airport, after passing through security, I went to put my shoes back on and, not unlike a sleepless princess fidgety from a pea 20 featherbeds down, I noticed some slight topography under my Dr. Scholl's insoles. I slipped my fingers in and found a single jigsaw piece. Blue. With dots. I put it in the outside pocket of my backpack and caught my flight. Two days later my sister and I went hiking in Placerita Canyon outside LA. At the furthest point of our route we sat down to rest. When we got up to head back I happened to look down. There was the blue puzzle piece, fallen out of my backpack. I grabbed it and wondered what would have happened had I missed it. A single puzzle piece, 400 miles from its origin. Who would find it and what would they ever make of it? How could they ever know what it was about or imagine the beauty of the painting it refers to?

| The Piece in Question |

So too in my standoff of stereotypes this week. I can stare at the tough across the table and simply stop there. But opening up to the holiness of our origins, or to some heart space that feels like that, I might perceive a deeper truth. Something about the life experience that drives someone to choose to show toughness rather than vulnerability. And the possibility that on deeper levels we're much more alike than we'd guess.

I may not be accurate in my speculations about this guy, but these intuitions are in themselves holy and, as Levi Yitzchak later suggests, they flow from the divine quality of rachmanut - or rachmones, compassion. The same spot on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life that is placed over the heart and gets to be nicknamed "truth."

If this connection to a greater truth is activated, then maybe it will work not just when I am reading the words or faces of others, but when I speak as well. Maybe it will allow me to convey more than the first impression I make, more than the stereotype I represent, more than the sum of my words. Maybe with it I could speak, even haltingly, like a tourist with a Berlitz, the Speech of Sinai. Maybe with it we could hear in each other a little bit of the kol, of God's voice, even if just for a moment.

May the Speech of Sinai come easily to our lips. So that when we speak to each other, our words lose their skins and dissolve into meaning, explode into possibility and tremble with holiness. And let us say: Amen.

Much gratitude to my chevruta partner, Reb Eli Herb of Durango, who stubborned through this difficult bit of Kedushat Levi with me, and to my sister, Lynn Keller, who made some key connections as we hiked and discussed God's voice.