For Congregation Ner

Shalom, and dedicated to the nursing and therapy staff of Santa Rosa

Memorial Hospital ICU and Neurology Ward.

I’ve

begun to take off my shoes at the hospital, in Mom’s room. I’ve taken to wearing

slip-ons for just this purpose. I’ve gotten comfortable here. It has been three

weeks after all, and our departure for the new adventure of a skilled nursing

facility is imminent. Here at Memorial, I know at least 40 nurses, doctors,

therapists and respiratory techs by name. I know many more by face. I know the

other most ardent bedside vigil family. We ask each other in passing about our

loved ones’ progress; we answer with noncommittal mutterings about daily improvement

– amejorándose cada día, gracias a Diós.

I

know the long traverse from bedside to bathroom to lobby to cafeteria. I love

the cafeteria food, even though it’s not really any good. I look at the beige,

crusted over fettuccini with vegetables, and I think, “Oh, it’s a bad night for

the vegetarians.” I think that until my eyes wander over to the tuna casserole

and I realize that it’s a bad night for everybody. But the food here is cheap

and made with sincerity, geared to feed hungry healers and anxious families,

and I can taste that straightforward intention. Less than four bucks later, I’m

back in Mom’s room, with a paper bowl of salty beans and rice and another of

carrots and, fortified, I can feel the kitchen staff at my back in this great recovery

campaign we’re waging.

Mom

has by now ended up in a private room. Not really private, just roommate-less. The

staff has been deflecting incoming patients to other rooms, because they’ve

grown fond of Mom, and her smile, and her laugh, and her family and friends.

They know we take up space, what with our books and our guitars and our food

baskets and photos and Shabbat candles and smuggled Manischewitz.

This

big, half-empty, soon-to-be-abandoned room has been imbued over this short time

with a kind of holiness. You can feel the room awash in it. So many people have

brought so much love into these four walls. And Mom absorbs it even when it

wears her out. We have chanted and read stories and coaxed out of her real

pitches and good stabs at pronouncing Gershwin lyrics with her limited

inventory of 5 vowels and 3-or-so consonants.

There

is a holiness in this room. The simple drama of life and death; the undeniable power

of word as demonstrated by its absence; the play of kindness, of chesed, mitigating the otherwise

unchecked tyranny of biology – all of this carries a force that feels epic and

ancient – and holy. There is a sense of the divine in moments of peril. “No

atheists in a foxhole,” they say. But I think what they mean is that you can’t

stand on that precipice of life and death and not feel the mix of hope and dread

that accompany danger. It may or may not be God, but perching on that threshold

of such elevated awareness brings with it an undeniable swell of grandeur.

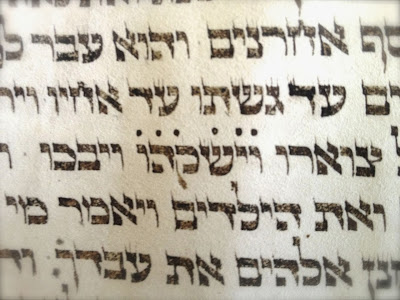

Mom’s

condition indeed has an epic, ancient quality – a biblical resonance. My

friends Dawn and Eitan Weiner-Kaplow pointed out to me this week that her left

temporal impairment is even described in Psalm 137, the “waters of Babylon”

psalm. The passage goes, “If I forget you, O Jerusalem, may my right hand

forget its cunning; may my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I do not

remember you, if I do not exalt Jerusalem above my chief joy.”

My

mother has never forgotten Jerusalem nor, to my knowledge, taken any vow re

same. Still, the context of the psalm – a song about grave loss – is apropos.

She has, like the Israelite captives in Babylon, lost her home. She has lost

use of the Temple that is her body. How can she sing her old songs in this admat nechar, this foreign soil, both the

foreign soil of California and the new, still uncharted normal of her own body?

First she must learn to sing again, period.

There

is much to lament in her situation. But grief and hope and uncertainty are as

holy as joy, and this room is palpably holy, so much so that I have begun to

remove my shoes, like Moshe in this week’s Torah portion, Shemot. Moshe, escaped

from Egypt and Pharaoh’s wrath, is now a shepherd in Midyan. An angel appears

in or as a bush that burns but isn’t consumed. (At Hebrew school I asked the kids

what that means. I asked who had a fireplace at home. Many hands went up. One

small girl piped up proudly that her family has two fireplaces. I asked her, “So

what happens to the wood that you burn in the fireplace?” She responded, “I

don’t know. Neither of them works.”)

In

the Moshe story, it’s unclear if the bush is meant to be a miracle, or just a

mechanism for getting Moshe’s attention. In order to perceive the bush wasn’t

turning to ash, he must have not only noticed it but stared at it for some

period of time, perhaps hypnotically, perhaps meditatively, or maybe just full

of scientific curiosity. In any event he slowed down, drawn into a different

kind of time, that holy kind of time that can move very fast or very slow, like

Alice getting big and getting small in the rabbit hole, but either way her

attention getting drawn to the unusual details around her. Once Moshe slows

down to this unusual shrinking and expanding pace, only then is the space

around him declared to be admat kodesh,

holy ground. And then, at that point, the shoes became superfluous.

I

asked the students why they thought there would be a “no shoes” rule in a holy

place, since it seems to be somewhat of a universal, whether the holy place is

a mosque or my German grandmother’s apartment. Some students were concerned

that shoes would mess up the site, leaving unsightly and disrespectful Nike prints.

Someone else suggested humility – that in the presence of God we are like

paupers before a great monarch; our shoelessness symbolizes that.

But

there’s also something else about how our feet, so seldom permitted nakedness, feel. Our hands touch and manipulate the

world all the time; they are for fiddling as much as for feeling; their

sensitivity is tempered and they are not to be trusted when testing the

bathwater. But our feet, so often sheathed in leather and canvas and rubber

are, when unleashed, open and guileless. Our feet feel for real; they transmit

sensation purely.

Which

makes our feet sensational organs for perceiving holiness. Whether the ground

is soft or hard, dry or moist, carpeted or tiled, when we slow our tempo, like

Moshe did studying the flame, we can feel so much from our feet. We can divine energy

emanating from the earth’s core, pouring up through our bodies, northward like

the Nile, and overflowing like the proverbial cup of Psalm 23. From earth into

body into spirit, with our feet as key synapses. This is the energetic conduit that

runs from sole to soul.

I

was listening to “To the Best of Our Knowledge,” on NPR the other night. It was

an episode called “Religion in a Secular Age.” They played comments from

callers about religion and one caller said, “Every day when my feet hit the

floor I experience the divine.” By which he seemed to mean that he felt the

divine from the moment he got up in the morning. But the metaphor, in which his

feet closed the circuit, really struck me.

I

think how my own favorite moments of the High Holy Days have come during ne’ilah, the closing of Yom Kippur, when

I give up any pretense of keeping shoes on, and stand before the closing gates

in my white Hanes athletic socks, trying to suck the holiness of the moment right

out of the ground.

Being

without shoes also allows me to climb into Mom’s hospital bed once in a while

to comfort her through a bad dream or some troubled breathing. My stocking feet

let me make the move from chair to bed smoothly, without it having to be a conscious

decision about care management or propriety. My feet simply lead, and I follow.

We

have a long road ahead. My sister and I are hunkering down. Mom is improving, and the doctors have retracted their direst speculations about the cause of her hemorrhage.

If she continues this way, God willing, we will at some point step off this

elevated threshold, step back from the precipice. Will our feet feel the

holiness even then?

In

the Torah portion, after Moshe’s shoes are off, after he and the bush have some

important chitchat about slavery and freedom etc., Moshe asks the name of the

holiness that surrounds him. God does not reply, “I am El Shadai, the God of the Mountain.” Nor “I am Haborei, the Creator of the World.” Not even “I am Hamakom, the World Itself.” But instead

something much vaguer, at once both a brilliant circularity and an outrageous

copout: Ehyeh asher ehyeh. “I am what

I am.”

Which

I choose to take as an invitation to notice the divine at any time in any

circumstance. “I am what I am,” “I am where I am,” “I am when I am.” Holy

ground is not a specified place to which one must make pilgrimage. And with all

due respect to Shabbat, holy ground is not limited to one day a week. Yes, you

might feel it extra on Shabbat, or in Jerusalem or Mecca or Rome or at the

lighthouse at Point Reyes. You might feel it extra in times of great danger, in

life-changing times. But it is also there in the ehyeh asher ehyeh experience – in the “whatever” moments.

As

we move off this precipice and on to the next phase of Mom’s recovery, I am

going to look for holy ground in the skilled nursing facility, in the rehab

gym, in the first swallows, in the words of slowly increasing intelligibility

and even in the frustration and tears when they don’t come. I look forward to

Mom’s – and all of our – admat nechar,

foreign soil, becoming admat kodesh,

holy ground.

To

do this I will try to remember to take off my shoes. Not my literal ones. But

to remove whatever barriers stand between me and the holiness of this existence.

Whether the barrier is leather or crepe; whether the barrier is work or worry. I

will do my best to remove the barriers that sheath my soul, so that I can feel the

holy ground beneath my feet. Whether that holy ground is a hospital room or a cafeteria

or a sidewalk or workplace or hiking

trail. Or sitting in the car with an unexpectedly dead battery on an

inconvenient day or some other stupid predicament.

After

all, Moshe found holy ground on the roadside himself, chasing a lamb that got

away from him. Inconvenient. Unexpected. He probably felt stupid. And even so, he

ended up on holy ground. He just slowed to the flow, staring at that bizarrely

intact bush defying the laws of thermodynamics. And I too will try to see

through those inconvenient, unexpected, stupid moments to spy what lies beyond

them. And maybe I’ll keep wearing slip-ons too, just in case.